Spatial Games

Auf dem Weg zu einer inklusiveren Planungspraxis

Teaching

See down below for results of the studio.

Im nächsten Sommer wird Berlin Gastgeber der Special Olympic World Games 2023, der weltweit inklusivsten Veranstaltung für Kinder und Erwachsene mit geistiger Behinderung. Die Eröffnungsfeier und die Veranstaltungen werden im Olympiapark Berlin stattfinden, einem Komplex aus Gebäuden, Sportanlagen und Parks, der für die Olympischen Spiele 1936 errichtet wurde. Die Anlage, die im Rahmen der politischen Propaganda für den „perfekten Menschen“ entworfen wurde, spiegelt noch immer den exklusiven Geist der Vergangenheit wider. In der Nähe befindet sich ebenfalls Le Corbusiers Unité d‘habitation von Berlin (Interbau 1957) mit der berühmten Fassadengravur des Modulor. Diesen Namen gab Le Corbusier dem geschätzten Durchschnittsmenschen, der als Maß aller Dinge dienen sollte. Das architektonische Gefüge um den Olympiapark mit seinen Achsen, Rastern, Ordnungen und Modulen kontrastiert stark mit der Idee der inklusiven Sportspiele, räumlich und gedanklich.

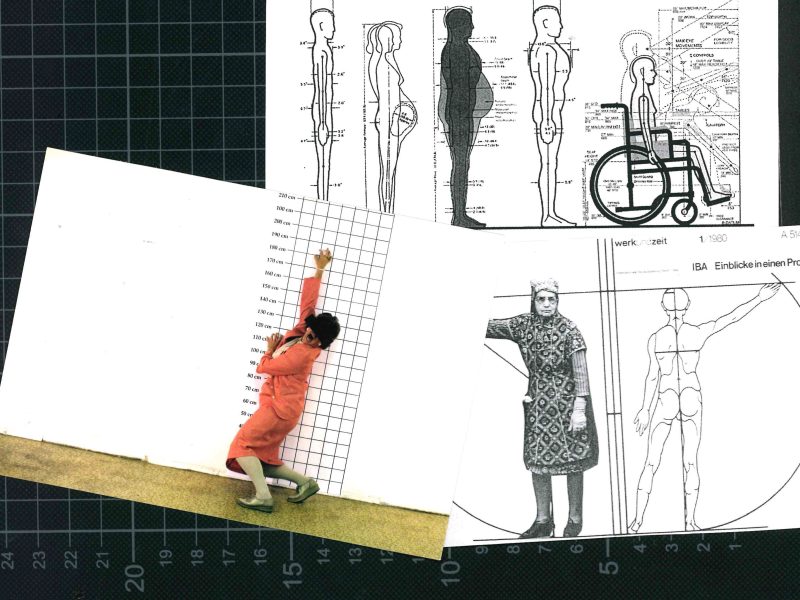

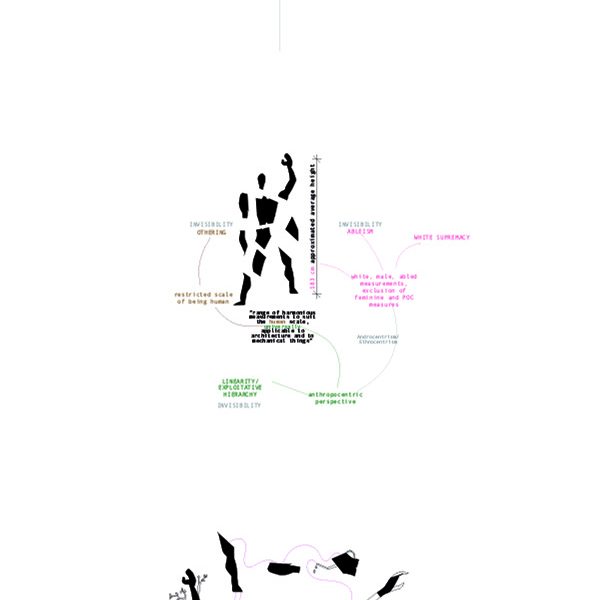

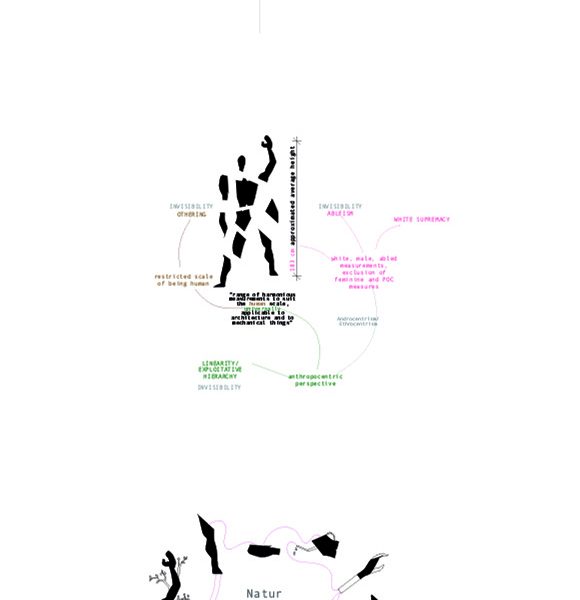

Im Studio „Spatial Games“ werden wir diese Kontraste als Ausgangspunkt nutzen. Die Idee ist nicht nur, inklusive Sportanlagen zu entwerfen, die für die bevorstehenden Spiele notwendig sind – mittels Theorien von Queering und Cripping wird das Studio ebenfalls versuchen, diesen Bereich als repräsentativen Raum der Inklusion neu zu gestalten.

Team CUD: Prof. Jörg Stollmann, WM Veljko Marković, LA Katrin Schömer, TT Leonie Hartung & Anna Barwanietz

—-

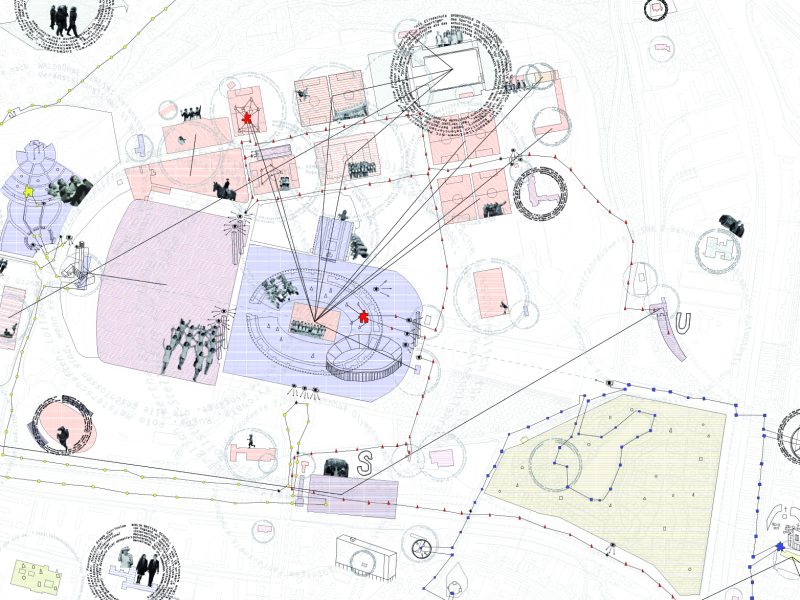

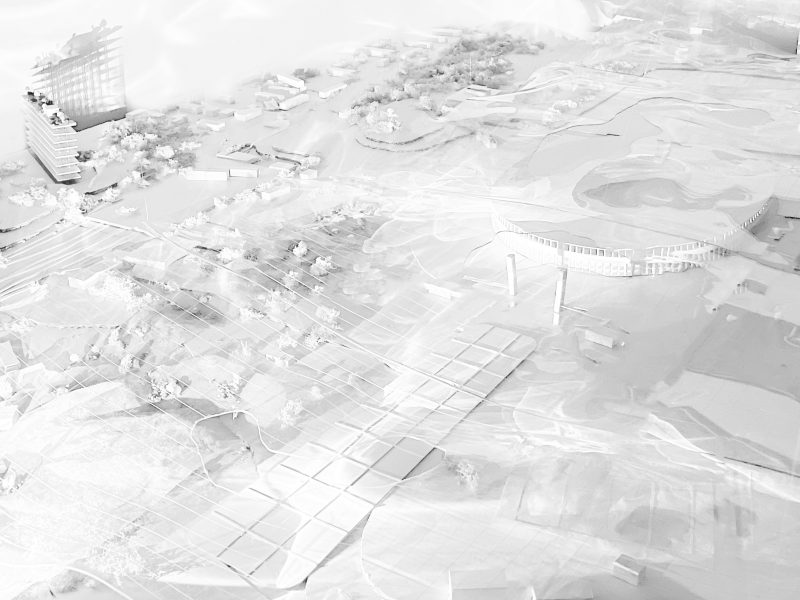

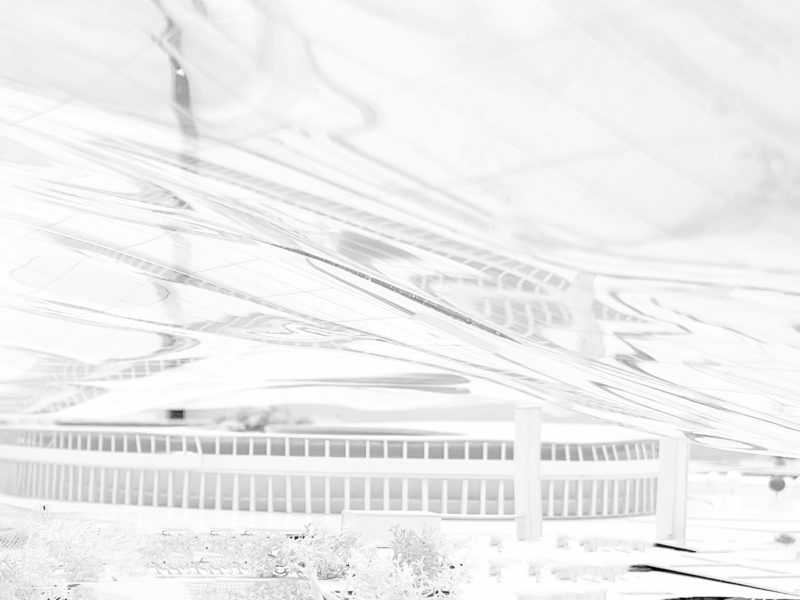

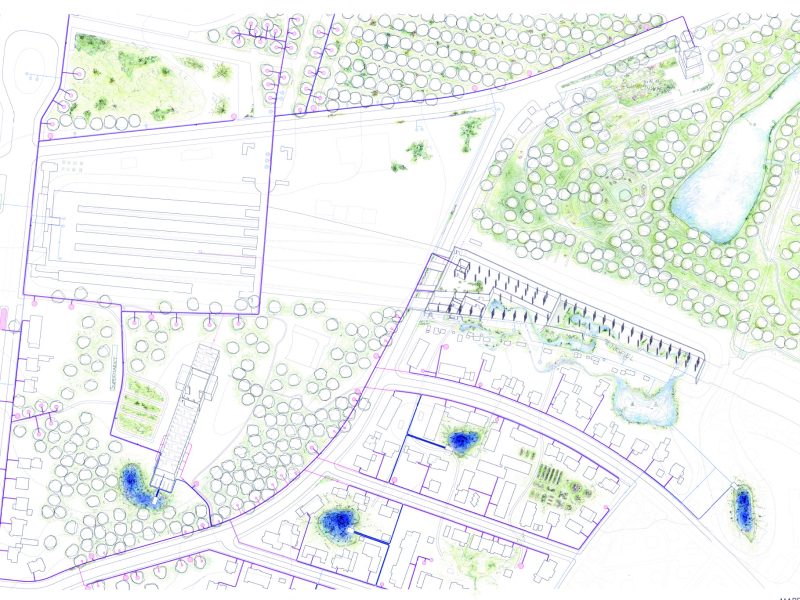

The first task in the studio involved using the “Nolli Plan” mapping method. Instead of visualizing the dichotomy between private and public space, the method was employed to envision and visualize accessibility borders from the perspective of “the others”, rather than one’s own spatial experience. The collage serves as a collective studio map of the area while also distinguishing individual student group work, each investigating a specific aspect of accessibility in their assigned quadrants.

Selected Student Projects:

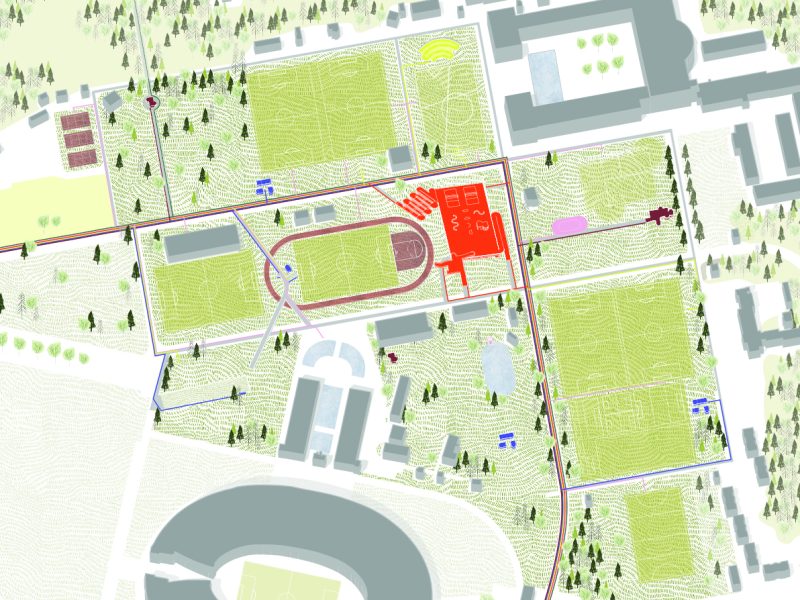

- Project Title: Olympia Park is not a “Club”

Students: Lukas Bogunovic, Nesma Grossmann, Matilda Hosemann, Anna Nagora & Kim Nguyen

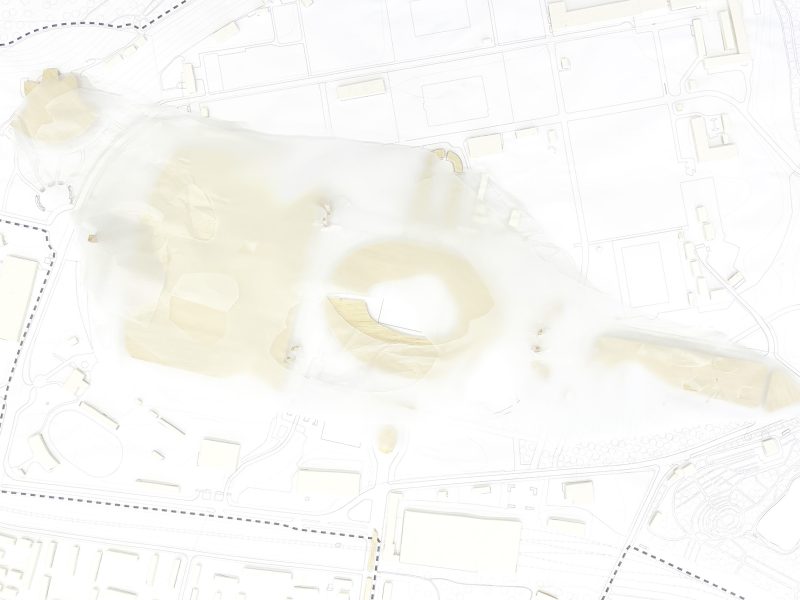

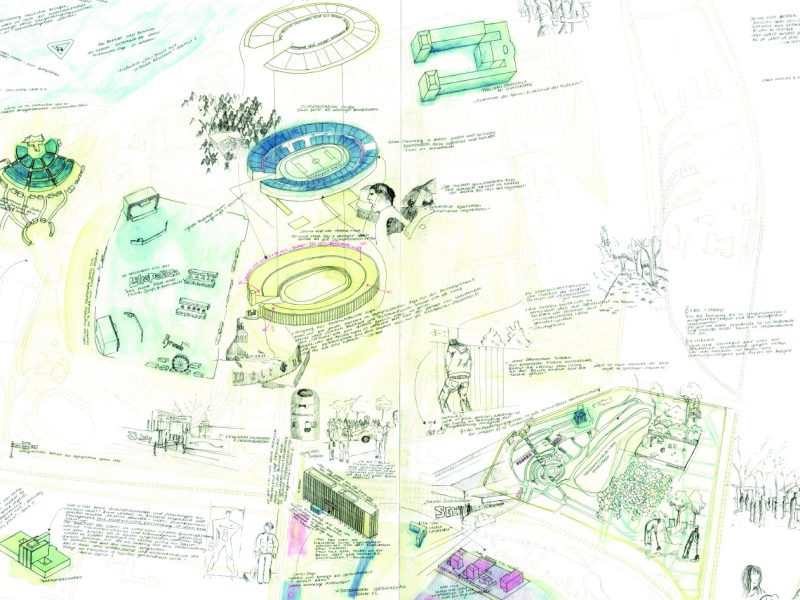

Upon the initial investigation of the accessibility of the Olympia Park area, although primarily perceived as an open space, a distinct culture of exclusivity in the form of “clubs” was identified through research. Everyday inhabitants, when confronted with this “Club culture” within the sports facilities, find it challenging to use the area as a neighborhood park. Rather than proposing significant physical changes, the project aimed to reorganize existing activities in a more inclusive manner, employing commoning as the spatial organizational tool. This method opens up free space for additional spatial interventions.

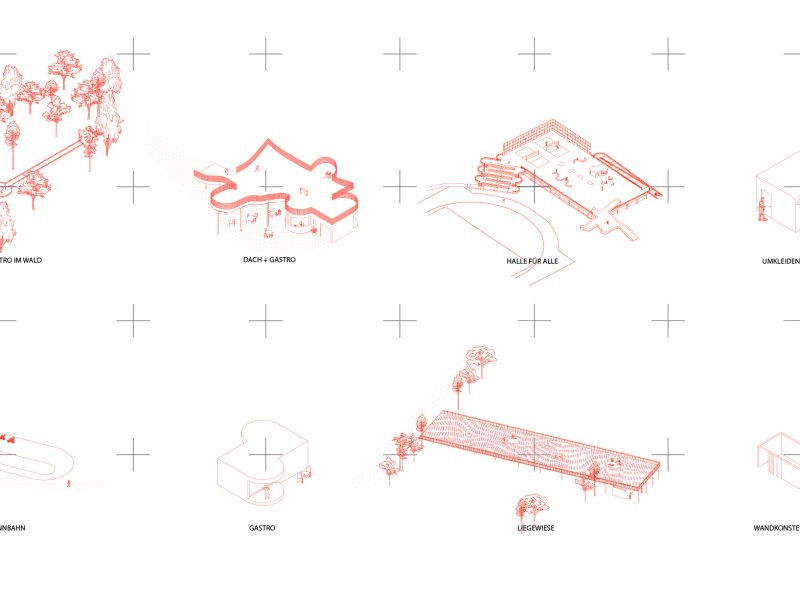

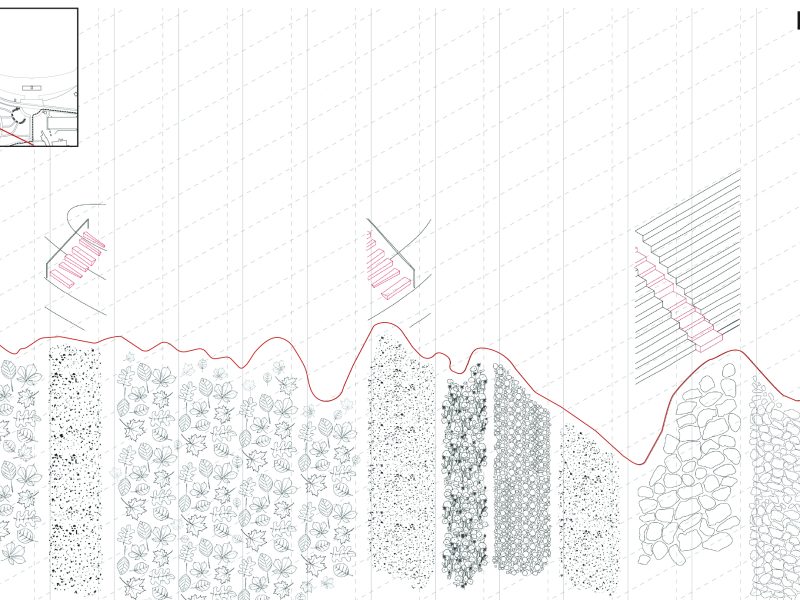

- Project Title: Next Layer

Students: Richard Bohlinger, Leonard Dähndel, Konstanze Habenicht, Anna Kozlova

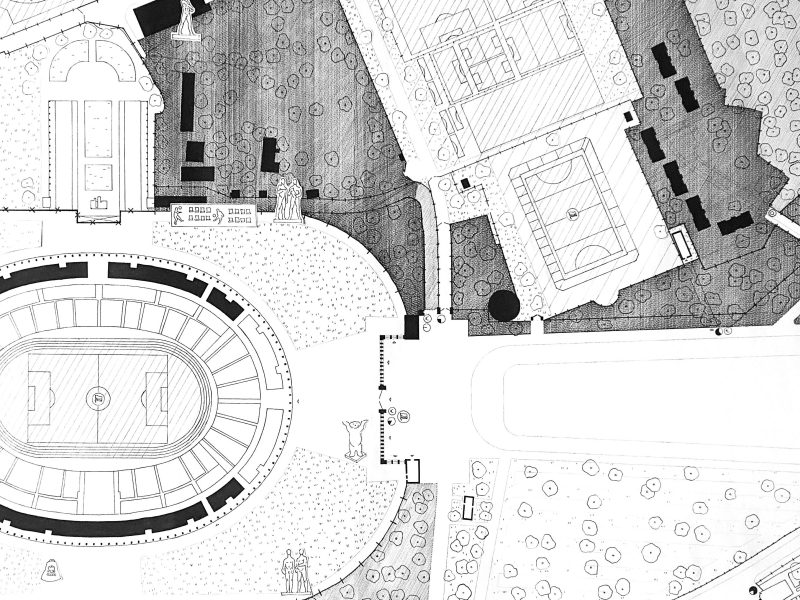

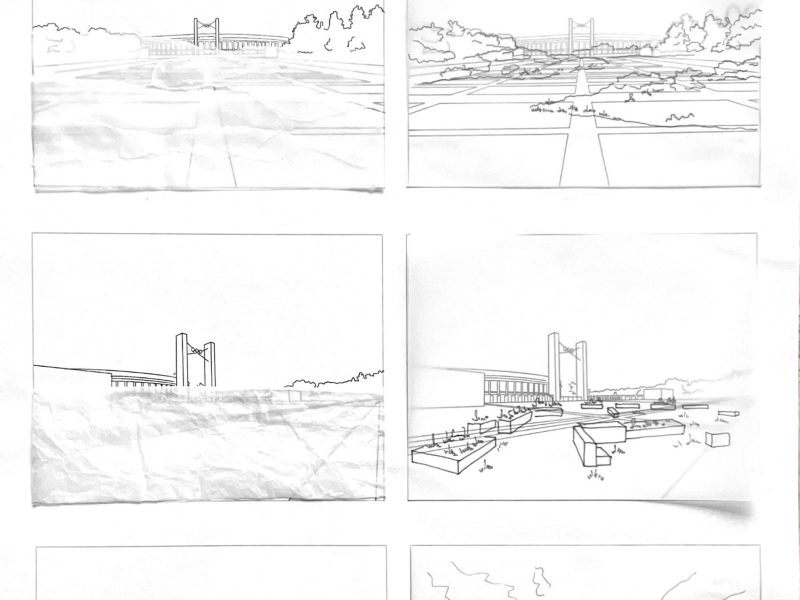

The student project was proposed as a way of addressing the inherited architecture and its symbolism through the subversion of its spatial perception. Instead of demolition, students suggested adding a new layer—a new layer for interpreting architecture and a new layer for standing ground. Initially intended as part of the opening ceremony for the Special Olympic Games, fragments of concealing and revealing architecture are envisioned as permanent installations.

Project Title: “Urinite”

Students: Djamila Hafner, Emma-Lu Huber, Maren Schomberg, Angelina Temp

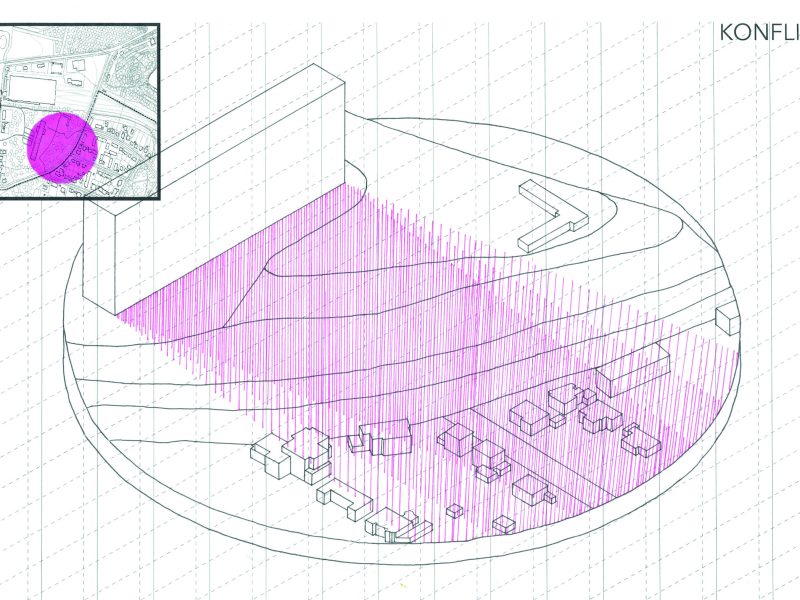

By observing and mapping the surroundings of Le Corbusier’s Unité d’habitation, students noticed a conflict between the icon of modernism and the initial inhabitants in the nearby surroundings. Specifically, the machine for living casts a shadow on the southern block of family houses. This power dynamic served as the starting point for developing a project called “Urinite.” Without proposing any demolition, the project aims to find ways in which the inhabitants on both sides can benefit from this conflictual situation. In the end, the project offers a fundamentally different reading of the architectural inheritance by exploring the infrastructural potential of the broader urban context. With this added function, the project challenges and subverts the idea of cleanliness in modernism as a paradigm.

(fig: 1) Image Credits: Sigrid Grajek as Coco Lorès; Image Source: Schwules Museum Ausstellung-of lesbian trans* gays and other normalities 2) Image Credits: Werk Und Zeit 1/1980; Image Source: 10 Jahre nach der IBA’87 Cataloge 3) Image Credits: Henry Dreyfuss - The measure of man; Image Source: Architectural Graphic Standards 1981)